As voters from Ohio to North Carolina to Georgia wait in long lines for hours to cast their early vote for president, onlookers abroad were left scratching their heads. That’s because in most other advanced democracies, long lines like these just don’t happen.

Canadians said they spent more time standing at bus stops than they do standing in line to vote, while Australians noted lines for their voting-day “democracy sausage” are longer than for the ballot box.

America’s long lines aren’t necessarily a surprise. Increased enthusiasm to vote early, especially among Democrats who want President Donald Trump removed from office, have swollen queues. Enhanced safety and cleaning protocols due to the pandemic, mixed with fewer and less-experienced poll workers, have caused delays. And voter suppression, from a dearth of official voting sites to dried-up resources in districts with large minority populations, has made it harder to cast a ballot this year.

Still, the multi-hour wait times show the US has a lot of work to do to make it easier for Americans to vote. In 2014, a presidential commission said no one should have to stand in line for more than half an hour, stating that “any wait time that exceeds this half-hour standard is an indication that something is amiss and that corrective measures should be deployed.”

Some of those measures could come from abroad, experts say. Countries like Canada and France have national voting standards that take voting-day decisions away from local partisans. Australia allows citizens to vote at any polling station in their area, not just one designated site. And Estonia, believe it or not, votes entirely online.

Adopting some of these practices might shorten voting lines in America and make it easier for everyone to cast a ballot, said David Daley of the pro-reform advocacy group FairVote. But the problem, he said, is that “we have been unwilling to look around the world to see who does it more efficiently and more fairly than we do.”

Here are some ways other countries handle their national elections, and what the US could learn from them.

The suggestion I heard most often from experts is that the US should have one single set of rules for how to administer elections in every state and territory.

“The US is unique in how decentralized our system is,” Ashley Quarcoo, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, DC, told me. “We have approximately 10,500 jurisdictions administering elections. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it does create challenges for ensuring electoral consistency, even service delivery, and a consistent — and ideally positive — experience for voters across the country.”

What’s more, local rules make it possible for the secretary of state — not the nation’s top diplomat, but a state’s lead official for voting — to stand for office while running the election. That’s led to controversies in Georgia and Kansas, with allegations swirling that both secretaries abused their power while simultaneously standing for another office.

In other words, the current American system increases the chances of corruption and a poorly run election. Having a federalized system — one where voting rules are the same across the country — could help fix that.

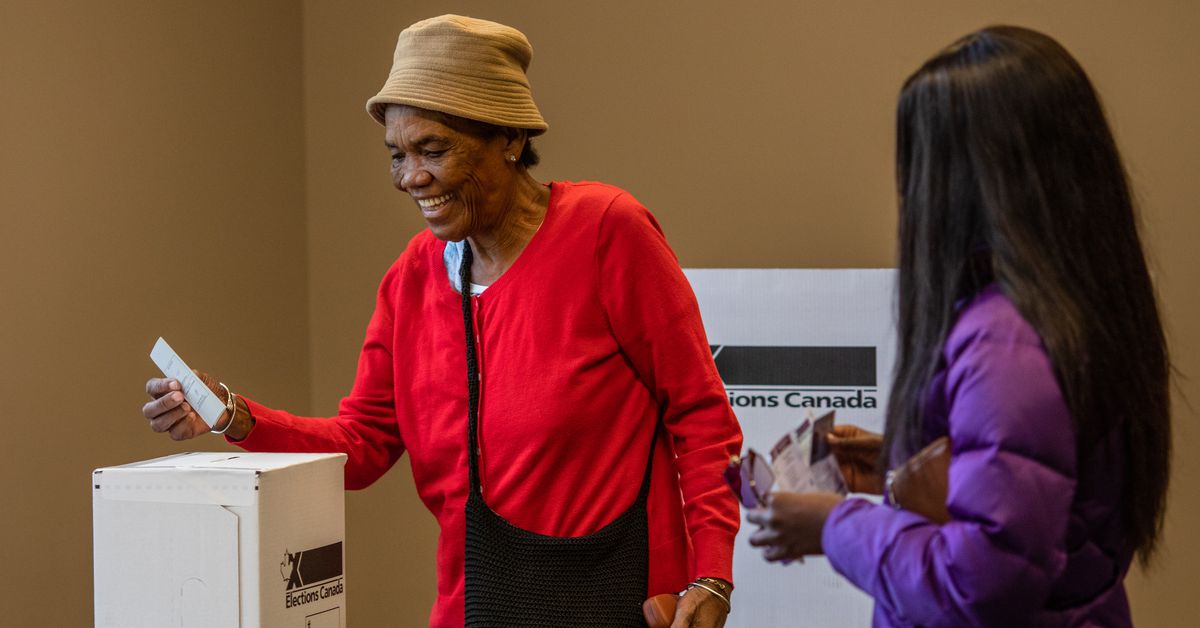

The US could look just over its northern border to Canada for inspiration. The country has a federal election system, which means that the voting process is the same from Halifax to Vancouver and difficulties are minimized (though there are still some related to voter ID).

One major reason it works so well is that Elections Canada, the government agency tasked with running national elections, is a nonpartisan, independent body. It can do its work without being tainted by partisan political concerns. The agency “is responsible for ensuring that election officers are politically neutral and non-partisan in all aspects of their work,” according to its website.

However, some experts are skeptical the US could have such an agency.

Staffan Darnolf, senior global adviser at the International Foundation for Electoral Systems, said central election authorities usually work well in countries that have them, but few nations have as divided a system as America’s. Instead, he proposes that each state’s most senior election administrator be a non-partisan election-administration professional.

“That’s a reform that could have a positive impact,” he told me.

In the US, a voter is typically required to cast their ballot at a specific location on Election Day. That’s not the case in Australia.

“You can vote at any polling place in your state or territory on election day,” reads the Australian Electoral Commission’s website. “Polling places are usually located at local schools, churches and community halls, or public buildings.”

And in case someone is traveling on Election Day, that person has another option at their disposal. “If on election day you are outside the state or territory where you are enrolled, you will need to vote at an interstate voting centre,” the website adds.

Put together, Australia makes it really, really easy for someone to vote by increasing the number of places they can stand in line to cast a ballot — which is a good thing since Australians are fined if they don’t vote.

Adopting this idea would make a lot of sense for the US as it would give voters the option to go elsewhere if they see a line getting too long. It also gives voters the flexibility to travel inside the country on Election Day without having to worry about being home to vote at their designated polling place (though they could alternately vote by mail).

But where Australia makes more polling sites available to voters, the US does the opposite. Last year, southern states closed around 1,200 polling sites; this year, Texas shuttered several official ballot drop-off locations.

Before America can have a conversation about providing more options to voters, it needs to first create more polling stations, period.

One of the most controversial reform ideas comes from Estonia, the small Baltic nation where citizens have been able to vote for their political leaders online since 2005.

“I-voting is possible around the clock during the days of advance voting, from the 10th until the 4th day before the election day,” the country’s electoral agency says on its website, though it notes online voting isn’t allowed on Election Day.

About 64 percent of eligible voters cast their ballots online for parliamentary elections in 2011, 2015, and 2019, which means the actual in-person lines to vote on Election Day are shortened. If nearly three in five voters in America could vote for their preferred candidate from their own computers at home or work, the multi-hour waits we see now at the polls would practically vanish.

The challenge, though, is ensuring the safety and integrity of the vote. “Online voting is just a horrible, horrible idea in the United States,” said Jason Healey, a cybersecurity expert at Columbia University. “Estonia can get away with it because they’re so small and use their digital IDs for almost literally everything, so voting is just one, rare use.”

Indeed, the digital ID every Estonian has allows them to travel within the European Union, serves as a health insurance card, gives them access to their bank accounts, and much more. It’s a highly advanced, encrypted system the country works tirelessly to perfect and secure. That’s a hard thing to do, but it’s made easier when the nation’s population is only 1.3 million people.

Meanwhile, America’s population is over 250 times as big, and it’s nowhere close to having such an integrated digital system to prove everyone’s identity across nearly every facet of someone’s life. The US could invest in such a system, but it would require political will, tons of money, and time.

It doesn’t look like the US will fully go in that direction, though. It’s already dealing with election interference from the Russias and Chinas of the world, and top political leaders including Democratic vice presidential candidate Kamala Harris still tout the benefits of paper ballots over digital ones.

But if the US could find a way to make online voting secure and reliable, it could prove the greatest game changer of all.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

The United States is in the middle of one of the most consequential presidential elections of our lifetimes. It’s essential that all Americans are able to access clear, concise information on what the outcome of the election could mean for their lives, and the lives of their families and communities. That is our mission at Vox. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone understand this presidential election: Contribute today from as little as $3.

"do it" - Google News

October 20, 2020 at 02:10AM

https://ift.tt/2He1qXo

US has long 2020 election lines. Canada, Australia have better voting systems. - Vox.com

"do it" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2zLpFrJ

https://ift.tt/3feNbO7

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "US has long 2020 election lines. Canada, Australia have better voting systems. - Vox.com"

Post a Comment