Gary Gragg is running late to an important meeting with his family, but he can’t stop talking about avocados.

Not just any avocados — he’s looking at enormous, cantaloupe-size avocados hanging from a tree in a small front yard in the East Bay. These are the largest avocados Gragg has ever seen grow in California, and they’re thriving on this otherwise unremarkable residential street. He knows this tree well but is so enamored with its fruit, it’s hard for him to tear himself away.

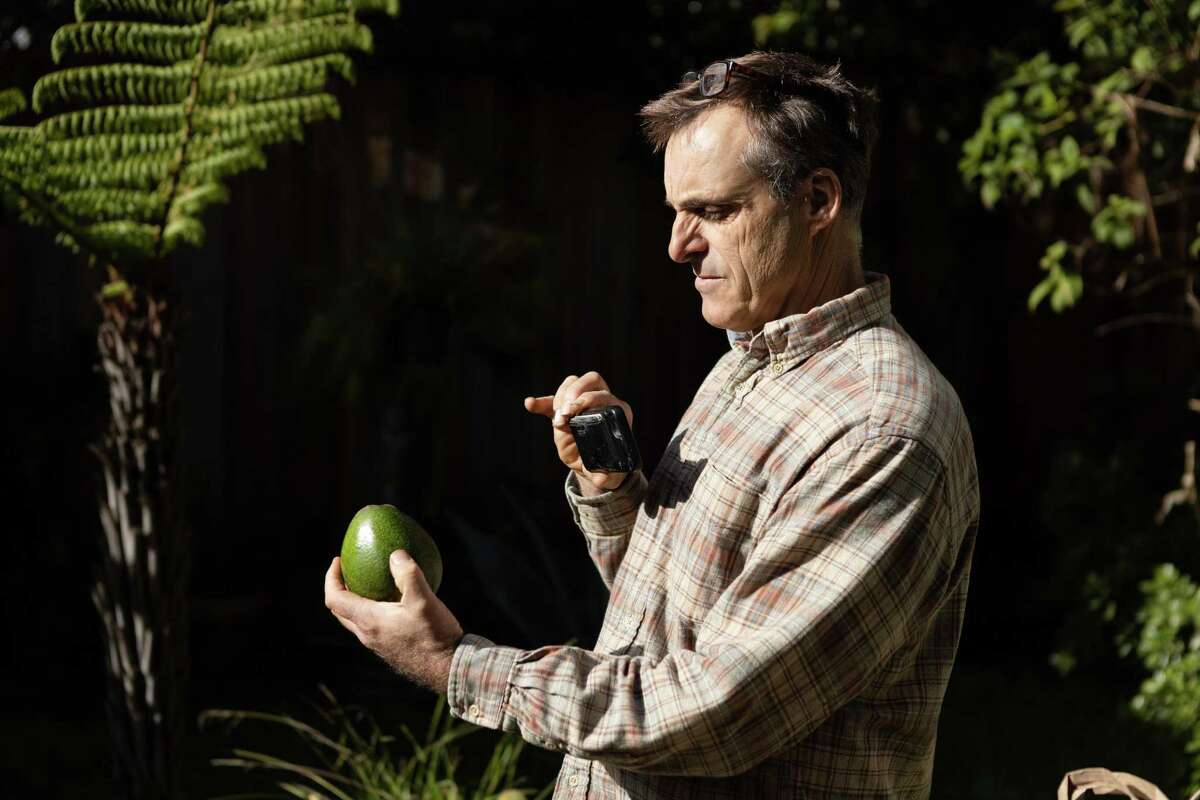

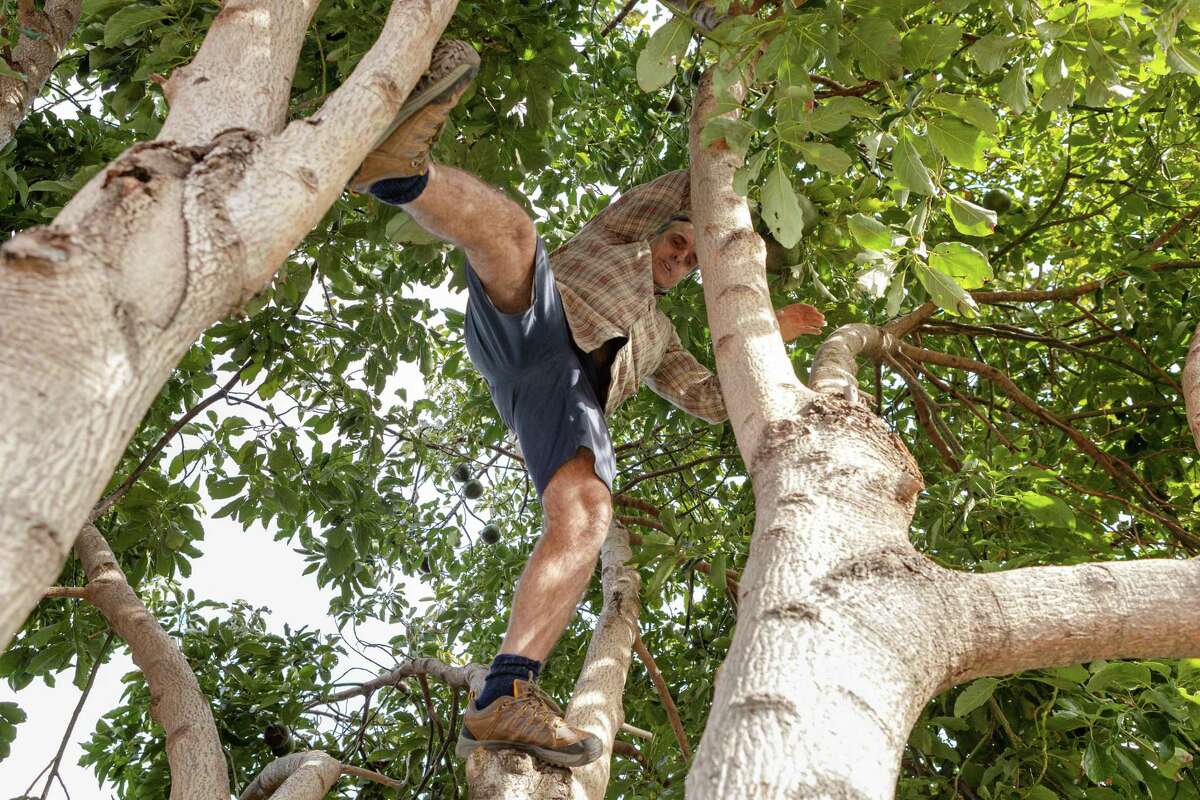

He shimmies up into the tree’s branches with unbridled excitement, filling his arms with the ripe fruit. He whips out his phone to document his prizes and starts talking emphatically about the tree’s genetics and the history of California avocado production.

Nerding out over a stranger’s avocado tree is a regular occurrence for Gragg, the 53-year-old owner of Richmond nursery Golden Gate Palms. He’s always on the lookout for avocado trees when he’s driving through the Bay Area, peeking through gates into backyards and knocking on doors to pepper owners with questions about the trees’ origins. Although a pervasive misperception has convinced many Bay Area residents that avocado trees won’t grow here, they’re all over if you know to look for them: poking out behind apartment buildings in Oakland, towering over San Francisco backyards and leaning over freeways in Hayward.

Gragg’s obsession has a purpose: He’s on a mission to fight avocado homogeneity. He’s pained at the thought of a future filled only with Hass avocados, the most prevalent variety and the one most commonly sold at grocery stores. He wants to find as many Bay Area trees as possible, propagate and sell them to keep them alive, just like heirloom tomatoes or apple varieties.

He spotted this particular East Bay tree several years ago while biking through the neighborhood. Its fruit is stunningly large, weighing as much as 3 pounds with super creamy, rich flesh inside. After that fateful discovery, Gragg returned to convince the tree’s owner to sign a written agreement that allows only him to propagate the tree.

“Diversity is out there,” Gragg said, “but it’s getting lost.”

Gary Gragg peels a ripe avocado while recording for his YouTube channel in the backyard of John Schaecher, a Pacific Heights resident, on Friday, January 14, 2022, in San Francisco, Calif. The huge avocado tree in the backyard of Ammar Swalim?•s San Francisco hardware store also provides to his neighbor, Mr. Schaecher, plenty of avocados.

Constanza Hevia H. / Special to The Chronicle

Gary Gragg cuts the leaves of an avocado tree branch in Ammar Swalim?•s San Francisco hardware store on Friday, January 14, 2022, in San Francisco, Calif.

Constanza Hevia H. / Special to The Chronicle

Gary Gragg records a video for his YouTube channel in the backyard of John Schaecher, a Pacific Heights resident, on Friday, January 14, 2022, in San Francisco, Calif. The huge avocado tree in the backyard of Ammar Swalim?•s San Francisco hardware store also provides to his neighbor, Mr. Schaecher, plenty of avocados.

Constanza Hevia H./Special to The Chronicle

Gary Gragg compares the size and texture of a Hass avocado growin gat his nursery with fruit from a backyard tree in San Francisco.

Constanza Hevia H./Special to The ChronicleAvocado obsessive Gary Gragg slices open a ripe avocado, clockwise from top left, in S.F. for a taste test; he trims the leaves from an avocado branch behind a hardware store in S.F.; Gragg holds three avocadoes from a backyard tree in S.F. and compares them to a Hass avocado from his nursery; Gragg makes a YouTube video with an avocado. Constanza Hevia H. Special to The Chronicle

Gragg has made avocados his life’s work, growing them in his own backyard, at his nursery and documenting his tree foraging in unfiltered YouTube videos filmed on his iPhone. He’s tapped into an enthusiastic corner of the internet, with some videos clocking in thousands of views and strings of engaged comments and questions. As one poster wrote: “People don’t so much like long videos unless it’s about avocados.”

On a family trip to the Hawaiian island of Maui last spring, viewers watched Gragg pull over to check out a roadside tree and enthusiastically bite into an avocado like an apple. He often enlists his children and family pets as taste testers on camera. The YouTube channel doubles as his nursery’s marketing and customer service, and the avocado videos outperform any other plant content he produces. (He’s well-versed in performing onscreen; he also once hosted a gardening show for HGTV.)

On a recent morning in San Francisco, Gragg, wearing his usual shorts and flannel shirt, was scooping up avocados that had fallen from an enormous backyard tree with the zealous enthusiasm of Steve Irwin hunting crocodiles.

“They’re everywhere! This is a big boy,” Gragg cackles as he cradles a large fruit, talking to his iPhone as he records a video. “I can’t tell you how much fun I’m having. This is just way too much fun.”

That was the first time Gragg met this particular tree, the subject of a Chronicle article last month. He was wowed by its size and the fact that it is bearing more fruit than its neighbors can eat despite that it’s largely not taken care of. It’s covered in ivy, which isn’t parasitic but is taking light away from the tree. It’s not clear that anyone regularly waters the tree.

Gary Gragg is a Bay Area native and avocado obsessive who eats three avocados a day.

Constanza Hevia H./Special to The ChronicleGragg is used to finding trees in this condition. He’s been informally foraging avocado trees since he was a teenager growing up in the East Bay. He likes to think he’s channeling one of his heroes, Wilson Popenoe, whom the USDA sent to Mexico and Central America in the early 20th century to hunt avocados and bring them back to California. Tree-hunting is a habit that’s persisted as an adult; his daughter Arianna, now a 21-year-old college student, remembers him pulling over on the way to soccer practice to check out trees.

“He can recognize them while we’re driving 80 miles (an hour) down the road,” she said.

Seven or eight years ago, Gragg stumbled upon a huge, largely neglected tree in East Palo Alto with a discarded mattress underneath it. He named the tree Big Mup, after Arianna’s nickname, and managed to propagate it before it was cut down to build apartment buildings. People can now buy and grow their own Big Mup trees from Gragg. The fruit has a thick skin and “voluptuous” shape that Gragg describes as sexy.

The East Bay tree with enormous fruit is a special tree whose location he keeps secret, not only to protect the owners’ privacy but his own investment. He named it the Gordo Gragg, using the Spanish word for “fat” in homage to the fruit’s enormous size. This unique Bay Area avocado variety may not end up in grocery stores, but that’s part of the point. Once customers are able to buy a tree in two years, they’ll be able to simply pluck one from their own backyard.

“The world is addicted to and expecting Hass avocados,” he said. “You gotta break the mentality of the herd.”

Gragg’s love for avocados was born decades ago at a Chevy’s restaurant. A young but savvy consumer, he knew how expensive avocados were and noticed there was no sign forbidding him from eating the avocados used to decorate the salad bar. He grabbed one, put a few creamy slices on his burger and never looked back. Gragg now proudly consumes three avocados a day, whether plain or in a bowl of guacamole.

Gary Gragg, who hunts avocado trees in his spare time, climbs a particularly fruitful tree in the East Bay.

Constanza Hevia H./Special to The ChronicleEventually, Gragg developed a fascination for horticulture, too. As a college student in San Diego, he filled his dorm room with plants and took on landscaping jobs. He’d collect exotic plants and bring them back to the Bay Area to grow in his mother’s backyard, which became his first, unofficial nursery. He now runs three large nurseries in Richmond, San Diego and Winters (Yolo County), home to more than a dozen varieties of avocado trees. Each is unique: Some yield large, oval fruit with thick, smooth skins; others are known for creamy flesh enveloped in thin, brittle skins. They have different seasons, and some larger, more expensive trees are sold with fruit already hanging from their branches.

Avocado trees make up just about 10% of his nursery’s sales, but they attract far more questions and engagement than other plants, Gragg said, with customers calling in years after purchase to ask for advice. (While avocado growers are far less common in Northern than Southern California, Gragg isn’t the only one. There’s also Epicenter Avocado Trees and Fruit in Santa Cruz County and an avocado grove in Humboldt County.)

Ryan Mason found Gragg several years ago when he was building his fantasy “guacamole garden” in his Oakland front yard, where he hoped to grow the core ingredients of guacamole. He bought two large avocado trees after watching many of Gragg’s charismatic YouTube videos. Though Mason has since moved to Montana, he still thinks about his two avocado trees that grew to 8 feet in part thanks to Gragg’s expert advice.

“He’s the most approachable, eccentric plant person I’ve met,” Mason said.

Homegrown avocados aren’t just delicious to eat; they also have an environmental benefit. Trees that grow in drier climates like San Diego require an enormous amount of water to survive. And when Hass avocados aren’t in season in California, stores meet the demand with fruit imported from Mexico, Peru or Chile.

“Why do we devote precious square footage of the earth, apply chemicals (and) displace native rich habitats ... for something that could be grown in your backyard with almost no care at all?” he said.

Gary Gragg peeks through a gate at a backyard avocado tree in Pacific Heights in San Francisco.

Constanza Hevia H./Special to The ChronicleSome might call Gragg’s obsession “excessive,” including Arianna. As long as she and her older sister Raea can remember, avocados have been the Gragg family religion. They grew up among their father’s backyard avocado grove. They turned avocados into homemade face cream and sold the homegrown fruit from the backs of cars at track meets. Their father never failed to embarrass them on airplanes, where he’d pull out a ripe avocado and use his credit card to slice off pieces of the flesh.

But Gragg’s unflappable passion rubbed off on his daughters. Arianna’s room at Dartmouth College is plant-filled like her father’s was decades ago — and home to 20 avocado seeds sprouting in jars and vases. She wants to work in ag-tech or at an environmental startup after graduating.

And Raea Gragg became known as the “avocado girl” at her Loyola Marymount sorority because she always had the fruit on hand thanks to her dad. She surreptitiously planted seeds throughout her time on the Los Angeles college campus. They were left unattended for well over a year during the pandemic, but she recently returned and found about five thriving avocado trees.

“I told him, ‘Every avocado seed you gave to me in college, I just planted it on my campus secretly in the middle of the night,’” she said. “He was so proud.”

Elena Kadvany is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: elena.kadvany@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @ekadvany

"filled" - Google News

February 08, 2022 at 07:03PM

https://ift.tt/e6Fuqtj

Bay Area yards are filled with mysterious avocado varieties. This man is on a mission to find them all - San Francisco Chronicle

"filled" - Google News

https://ift.tt/03PCQwO

https://ift.tt/E5tH4j0

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Bay Area yards are filled with mysterious avocado varieties. This man is on a mission to find them all - San Francisco Chronicle"

Post a Comment